Recently I spoke at a TEDx event about the need to support young people struggling with mental health issues. To mark World Mental Health Day, I have decided to adapt my talk into a blog post.

Please also see the joint Globe and Mail op-ed piece that University of Toronto Chancellor Michael Wilson and I wrote about this important topic.

If you need personalized support or are concerned for a fellow student, friend or family member at UBC, please visit students.ubc.ca/counselling.

I’d like to tell you about two young men. They were very similar in many ways. Both were studious, shy university students. But there was one crucial difference. The one on the right, Brogan Dulle, took his own life. The one on the left, Santa Ono, tried to do the same – twice – but he didn’t succeed.

I was 14 years old the first time I tried to take my life. I was desperate and I was depressed about how I was doing in school.

I’m very grateful I woke up the next day.

I again tried to take my own life as a young academic at Johns Hopkins University. I was depressed because I had tried to get an experiment to work for several months and it seemed like every single time I tried the experiment wouldn’t work.

I struggled with mental health issues throughout my youth and young adult life, including my years at the University of Chicago, McGill University, John Hopkins University and Harvard University.

Finally, I was hospitalized in Baltimore and that’s when things got better. I was seen by individuals who diagnosed me properly and through a period of about a year and a half, I had the appropriate medical support, psychological support.

I was diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder, a mental disorder that affects more than 5.7 million American adults. People who have this disorder experience episodes of depression followed by manic, or overexcited, episodes. In most cases, this is a chronic condition that persists over one’s lifetime. Approximately 20 percent of bipolar individuals attempt suicide.

In my case, I was treated with a combination of psychotherapy and Zoloft. I think the reason I have been successfully treated (and symptom-free for decades) is that I had a mild form of the disease, with hypomania and mild depression. Maturation, better work/life balance, better nutrition and sleep patterns, and an understanding of childhood stresses were also important in my recovery.

For the last 25 years, I’ve been symptom-free. A big part of the balance in my life is that I have a loving family, and they’re there for me.

Not everybody is so lucky. Brogan Dulle, the other young man in the image above, for one. Brogan was a 21-year-old student at the University of Cincinnati, and a part-time swim coach. He left his apartment around 2 a.m. on May 18, 2014, telling friends he wanted to retrieve a cell phone he had lost earlier that evening.

He never returned.

Eight days later — after a massive search— his body was found in a nearby building. He had used a crowbar to break into the building where he went down into the basement and hanged himself. I was president of the university at that time and his death affected me, and the entire University of Cincinnati community, deeply.

We never found out why he took his life or what was troubling him.

His parents, his four brothers and his sister are still searching for answers to that question.

After Brogan’s death, I became more outspoken about my own experiences, hoping that my example would help others realize that they’re not alone and that depression is nothing to be ashamed of. I wanted to ensure that the Brogan Dulles of the world get the support they need to lead healthy and fulfilling lives.

When Brogan was teaching young children how to swim, he would often tell the story about the little engine that could, to encourage them to do their best.

As Brogan told the kids, we are all little engines that can. However, for some of us — especially people suffering from mental illness — the hills are that much steeper, and sometimes we need help to get up those hills.

But to get that help, we need to remove the stigma around mental health.

If you get the flu, or break a leg, you don’t hide your illness or injury — you seek medical aid.

But if you’re mentally ill, you’re less likely to seek help, because of that stigma — the sense that mental illness is something to be ashamed of, that it’s your fault.

But you may be wondering whether this is really a serious problem. Most young people seem to exude good health. Is mental illness really such a problem for adolescents and young adults?

The answer is yes. Mental illness is a major problem for young people. In fact, mental illness — depression in particular — is the largest cause of disease among young people, according to the World Health Organization.

In some cases, this can lead to suicide. For others, it may mean higher alcohol, tobacco and drug use, adolescent pregnancy, dropping out of school or delinquent and antisocial behaviour.

There are many people and organizations actively trying to do something about the epidemic of mental illness among our young people, working to take the stigma out of mental illness and to help those who are afflicted.

To help us get over those hills.

Here in Canada, the federal government recently announced a $5-billion commitment to support mental health initiatives across the country – focusing in particular on young Canadians. And the Canadian Mental Health Association launched its b4stage4 campaign, with a focus on prevention, early identification and early intervention.

For those of you who don’t know, there are four stages to mental health conditions ranging from the mild – stage 1 – to the severe – stage 4. The b4stage4 campaign is aimed at getting intervention before people reach stage 4. You can find out more about this important campaign at b4stage4.ca.

Other countries are also taking action. For example, in the United Kingdom, Prince Harry and Prince William have spoken publicly about their own struggles with depression following the death of their mother, Princess Diana.

Together with the Duchess of Cambridge, they have started the Heads Together campaign, which wants to help people feel much more comfortable with their everyday mental wellbeing and have the practical tools to support their friends and family.

I am heartened to see all these initiatives at the international and national level. But more action is needed, by all of us.

Students in particular need our support, because they are at a vulnerable period in their lives – a period of great changes and upheavals, and a period when passing and failing has serious consequences.

I am glad to say that universities and schools, including UBC, are taking action.

For example, at UBC, the Thrive program aims to build positive mental health for everyone — students, faculty and staff. You can learn more about Thrive at thrive.ubc.ca. (And be sure to check out Thrive Week, starting on October 30.)

One important element to successful university and school mental health programs is peer support. No one knows the pressures that students face better than other students. Students are also more likely to trust advice given by other students. That’s why UBC — and other universities — put resources into peer support.

We’re also using social media to reach out. We often hear about the negative effects of social media on mental health — and those effects are definitely real. Cyberbullying, social isolation, screen addiction — those are serious issues. But social media can also be a positive force for young peoples’ mental health, and it has to be an important part of our mental health strategy for young people.

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat — are all being used to reach out to young people, and provide them with the help they need.

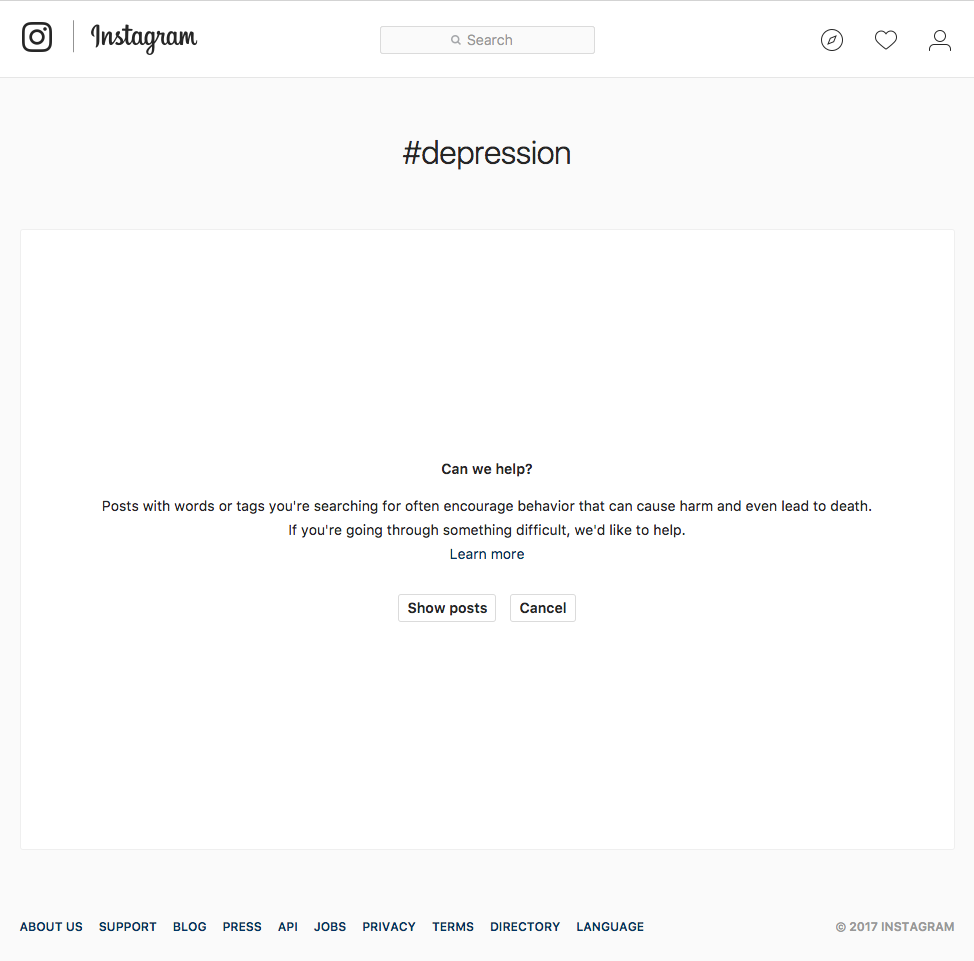

For example, if you type #depression in Instagram, the app shows this screen:

Facebook does something similar, and Google recently announced that users in the United States who search for “depression” or “clinical depression” will be offered a questionnaire to test their depression levels and help determine whether they should seek professional help.

Here in Canada, organizations like Bell Canada are actively using social media to engage in the conversation about mental health. Since it started in 2011, Bell’s Let’s Talk campaign has resulted in hundreds of millions of interactions, the allocation of millions of dollars in funding to mental health support and — most importantly — a national conversation about the importance of mental health.

But it’s not just the Facebooks and Bell Canadas of the world that can make a difference. Individuals like you and me also play a role.

Whether you’re a parent, a teacher, a friend, a sibling, if someone you know is vulnerable, you can help. Here are some useful tips from UBC’s Thrive website:

- Know the warning signs: Contact a mental health professional or call 1-800-SUICIDE (1-800-784-2433) immediately if you or someone you know exhibits one or more of the following:

- threatening to hurt or kill themselves, or talking of wanting to hurt or kill themselves,

- looking for ways to kill themselves by trying to get firearms, pills, or other potentially lethal instruments, and/or

- talking or writing about death, dying, or suicide (if these are out of the ordinary for the person).

- Contact a mental health professional or call 1-800-SUICIDE (1-800-784-2433) as soon as possible if you are concerned about someone who exhibits one or more of the following:

- experiencing overwhelming emotional pain and hopelessness,

- feeling hopeless,

- feeling rage or uncontrolled anger, and seeking revenge,

- acting reckless or engaging in risky activities, seemingly without thinking,

- feeling trapped, as if there were “no way out”,

- using alcohol or drugs increasingly,

- withdrawing from friends, family, and society,

- experiencing anxiety, agitation, or sleeplessness, or sleeping all the time,

- having dramatic mood changes, and/or

- feeling that there is no reason for living and having no sense of purpose in life.

(There are lots more resources on the Thrive site.)

We’re all like the little engine that could but sometimes we need help in getting over those hills.