Ways to prevent sexual violence include recognizing and stopping behaviours/actions that normalize it. We each have a role in creating a culture of accountability and consent on—and beyond—campus.

This post includes mentions of sexual violence that could feel upsetting. If you need help or want to talk to someone about sexual violence, UBC’s Sexual Violence Prevention and Response Office (SVPRO) and AMS Sexual Assault Support Centre (SASC) are here for you.

January at UBC is Sexual Assault Awareness Month (SAAM), a month of events put on by campus groups that engages the UBC community in conversations about sexual violence, and behaviours and norms that can contribute to it.

We can help prevent sexual violence by actively challenging myths and assumptions about it, and by changing the narratives and attitudes around us. Small, everyday actions can help build a culture of accountability—and keep the campus a safe, respectful space for everyone, the way it should be.

What is sexual violence?

Sexual violence can happen to anyone, regardless of gender, sexual orientation, or circumstances. It can be physical or non-physical, and can include but is not limited to:

- Sexual assault

- Sexual discrimination and harassment

- Physical/cyber stalking

- Stealthing (non-consensual condom removal)

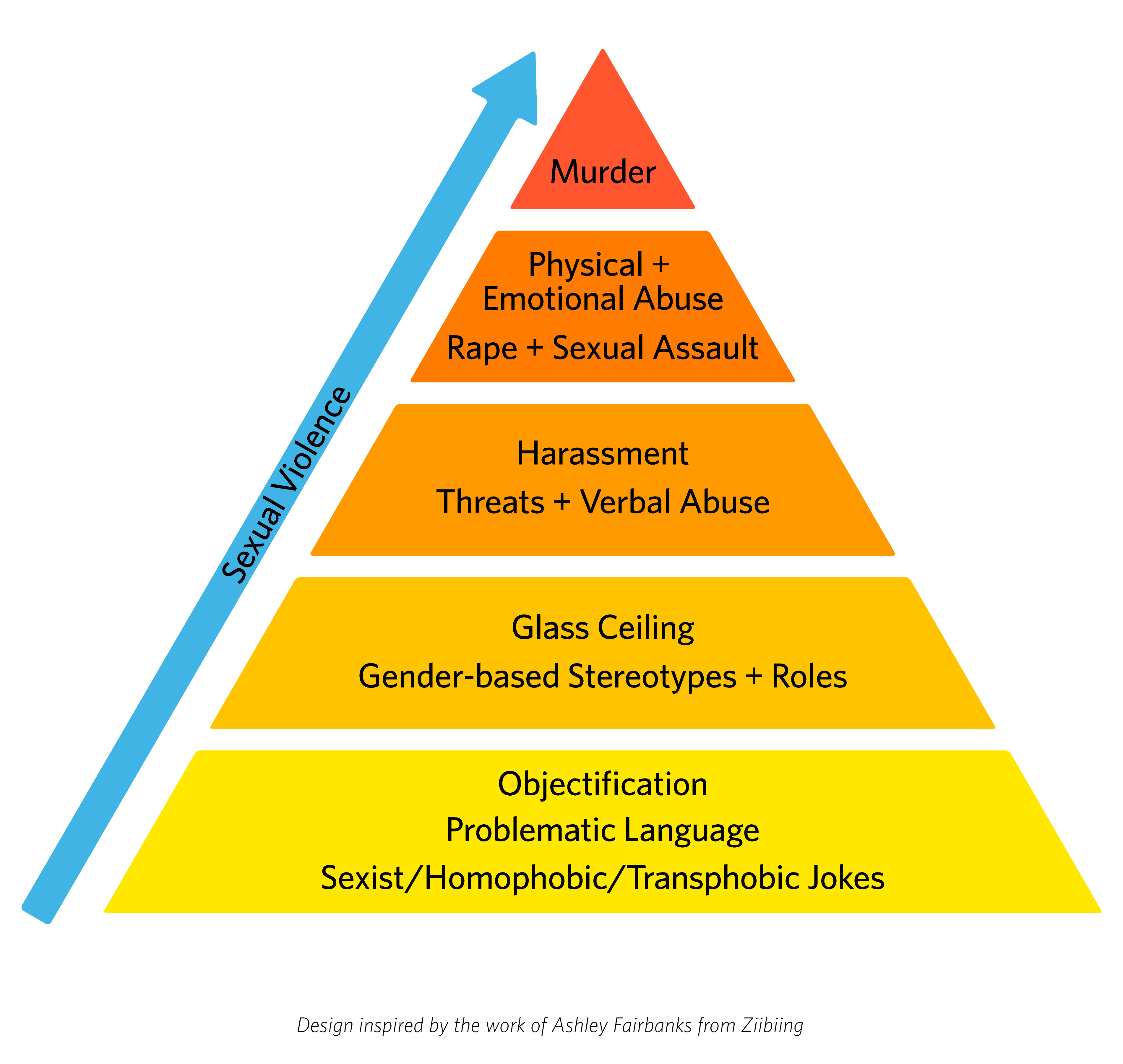

Sexual violence happens in a culture where it is normalized and even seen as not preventable. Sometimes, our own attitudes and behaviours (while seemingly harmless) can actually contribute to this normalization of rape culture.

UBC takes sexual violence very seriously. That’s why a Sexual Misconduct Policy SC17 (formerly Policy 131) exists, updated July 2019. In it, sexual misconduct is defined as “any sexual act or act targeting an individual’s sexuality, gender identity or gender expression, whether the act is physical or psychological in nature, that is committed, threatened or attempted against an individual without that individual’s [c]onsent.”

To help you better understand sexual violence, and what actions you can take to prevent it, we talked to 4 students who’ve been working to challenge sexual violence and behaviours/norms that perpetuate it.

What sexual violence can look like—behaviours that contribute to it

Here are just some examples of behaviours that can be contributors to sexual violence:

1. Rape jokes, references to sexual assault as metaphors

Using “rape” as a joke or a metaphor to describe unpleasant experiences that have nothing to do with rape (e.g. saying, “That exam raped me”) normalizes and trivializes the very serious offense that is sexual assault.

“From an outside perspective,” says Michaela, a 4th year Arts student who’s on The Calendar team and currently involved in raising awareness about bystander intervention in party culture, “it’s visible in how it’s wrong...but sometimes the people involved do not always realize what they're saying is contributing to a culture that we are all trying to put an end to.”

2. Locker room talk

Michaela’s played many competitive sports, and isn’t new to locker room talk. She’s witnessed (during late elementary school) “girls and boys bragging about how many people they’ve kissed to ‘one up’ their peers.” As time went on, this kind of talk escalated into:

- “Look at how many people I’ve dated”

- “Oh, I’ve hooked up with all these girls”

- “How many guys do you think I can make out with at the party tonight?”

Michaela’s also heard people bragging in ways that dehumanize/objectify their partners, such as “using degrading names regardless of how they feel or felt about them, making them sound like objects for sex, and focusing primarily on their technique, body parts, or ‘how good’ they were...as if to completely remove identity, like nothing else matters.”

3. Victim-blaming

Telling survivors what they should and shouldn’t have done, or asking them why they didn’t just “do something” are just two examples of victim-blaming. We should instead hold the perpetrators accountable.

“Some people have the response, ‘They were drunk, they should’ve been more careful or responsible,’ when they hear that someone was sexually assaulted at a party,” Michaela says. “Others often have the same response to clothing, like ‘their skirt is too short, they’re asking for it.’ It’s never the victim’s fault and these responses are not okay.”

4. Slut-shaming

To Shiayli, a 4th year Arts student and a Student Educator with SVPRO, slut-shaming is a pervasive issue, particularly among women. “There are so many messages in our society that teach girls how to dress and act to be ‘respectable’ or to stay ‘safe.’ When something happens, I find we often judge other women the same way we have been socialized to police our own behaviour.”

What you can do to prevent sexual violence

Sexual violence can be prevented by stopping behaviours and actions that normalize it. We all have a role in creating consent culture on campus—and beyond.

Here are just a few everyday ways you can help prevent sexual violence:

1. Be aware of your own actions and behaviours

To prevent sexual violence, pay attention to how you act around others and how you bring consent into your own interactions. This can mean:

a) Pausing before you make a potentially insensitive comment.

You might have someone nearby who’s been harmed by sexual violence—whether or not they “match” your image of a survivor. They might’ve just not disclosed to you their situation. Be mindful of what you say and bring up in the presence of others; avoid using language that contributes to slut-shaming, e.g. “hoe” and “that’s what she said.”

b) Practising consent, respecting boundaries in your own relationships.

“Be willing to be rejected without making a fuss,” advises Kaurwn, who’s currently a Peer Mental Health worker. “Make consent a priority in every situation, not just sexual. Ask permission before giving hugs, offering advice, venting about something heavy. Make sure nobody ever has to say 'no' twice.”

If someone declines the first time, accept that. Don’t keep on asking them with the intent of pressuring them into saying “yes.”

And, as pointed out by Navika, a 3rd year Science student who’s worked as a Residence Advisor, “It’s important to understand that consent must be asked for and given at every stage of intimacy and that engaging in one act doesn’t imply that someone is ready to go beyond.”

2. Be an active bystander

In situations where you hear someone say things that you feel are contributing to sexual violence, avoid joining in—instead, try:

- Telling people that what they said was inappropriate and not funny

- Asking people why they said that with a simple “Did you really mean that?” so they might reflect on their words and actions

- Intervening if you feel that someone may be in an unsafe/uncomfortable situation, e.g. receiving unwanted advances

Here’s a video from The Ubyssey for more ways to be an active bystander:

3. Bring perspective into your circle of connections

As Shiayli asserts, you can talk to others about ways to prevent sexual violence. “Everyone brings unique insight, which can be knowledge about their peer culture and certain spaces and groups. You can start to make a difference inside circles that no one but you occupy.”

For her, it’s her involvement in sports: “I was able to take my interest in the anti-violence movement and start making a difference by starting conversations and getting my teammates and other athletes involved. Knowing that I can contribute in a way that no one else can has been my inspiration to continue in this work.”

You don’t have to be an expert or highly involved in support organizations to make a difference. Take steps to build a consent culture that everybody deserves, and help others do the same.

Drop by a SAAM event or workshop this month, and take what you learn wherever you go. If you are interested in going a step further, reach out to campus organizations like SVPRO and AMS SASC to learn how you can help.